We were warned.

For years, companies like Gallup cautioned that the vast majority of our employees were disengaged from their work. Researchers showed us that this lowered productivity and morale, and increased absenteeism and employee turnover. They said that large chunks of our workforce were considering changing jobs or careers.

And they placed the blame squarely on managers. They said that more than 80% of our managers weren’t qualified to manage people. They found that only about 20% of people have natural management ability, and that few companies have a way of detecting that ability in their managers.

They pointed to the roadblocks keeping companies from solving the problem: flawed hiring practices, an antiquated promotion process, and entrenched, old-school leadership.

We all nodded when we heard the axiom, “People don’t quit companies, they quit managers.” But we didn’t really see it.

Sure, improved employee engagement would be nice, but would it really translate to the bottom line? How could we prove it? Lower turnover would be nice too, but the rate of people leaving their jobs stayed pretty steady, so we figured turnover was an inevitable part of running a business. And the true cost of that turnover was difficult to measure. It wasn’t like our sales dashboards and budget reviews that gave us a clear view of profitability. Those were the things we measured, therefore those were the things that mattered.

So, we kept bad managers in place. If we even knew who they were—how many companies have a way of rooting out their bad managers? And even if they did, what hard-nosed executive would spend time and resources developing so-called “soft skills” in the absence of a demonstrated, direct link to financial performance? They’d be laughed out of the boardroom.

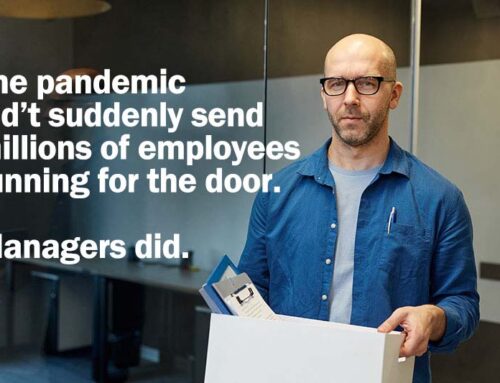

And then came the pandemic. Overnight, the world changed.

Businesses shut down. Employees who could, stopped going to work in person. Buying patterns changed. Nothing was predictable anymore and nobody knew if things would ever return to the way they were.

But as uncertain as those first few months were, we adjusted. The more we learned about the virus, the better we became at managing it. Our fears subsided. We’d fired or furloughed millions of employees, so we began hiring them back as things improved. Business began returning to normal.

And then our employees started quitting. We heard terms like “the great resignation,” and “pandemic epiphanies,” and we found ourselves powerless to stop the exodus.

The people we’d always assumed were grateful to have jobs suddenly decided they didn’t want them. When we let them go at the beginning of the pandemic, we gave them time to reflect. We gave them more time with their families and hobbies, the things that bring real value and pleasure to their lives. Then, they started comparing their new lives to their old ones: the intractable toxic workplaces, abusive managers who were free to carry on unchecked, distant and detached leadership. They remembered the price they paid to have those jobs—the commutes that took hours, the mistreatment they endured, the instability of jobs that can suddenly evaporate at an executive’s whim—and many of them decided their paychecks came at too high a cost.

And finally, way too late to do anything about it, some companies began to see how employee engagement and quality managers can impact the bottom line, and in a big way. Businesses curtailed working hours, too short on staff to return to pre-pandemic operations. They endured supply chain scarcities as their vendors suffered from labor shortages of their own. Bare shelves, unfilled orders, and sales backlogs were suddenly common.

That’s the cost of bad managers and low employee engagement, and it’s devastating. And now that we know, now that we have the evidence we’ve always needed, our organizations must change.

We can’t assume we’re ever going back to the way things were. It’s just not possible that one day, employees once again will be grateful to have jobs and will be desperate to keep them, no matter how high the cost.

We must do the hard work of rooting out poor managers and setting standards for respectful workplaces that cultivate and reward individual achievement and innovation. We must look at pay, benefits, flexible work schedules, and our own corporate citizenship, and we must make sure we are competitive. For we must compete not only with other employers, but we must also compete for time with families and personal activities, and when we get that time, we have to be worth it.

We must provide our employees with genuine job satisfaction. We must let them be involved in the business. They must feel like they have a stake in the company’s success. We must make workplaces safe for new ideas, questions, and innovation. We must listen to our employees and engage with them.

Our employees are the people at the heart of our business. More than our factories or computers or customers or shareholders, our employees are responsible for our success.

Let’s start treating them like it. Let’s give them better managers.

To learn more about how to be a successful manager, read Don’t Be a Jerk Manager: The Down & Dirty Guide to Management. It’s the management training you never got, available on Kindle and in paperback from Amazon.com.

Do you think you might be a jerk manager? Take the quiz!