In all areas of life, incentives work really well. They’re easy to understand—if I do this, I will get that—and they focus people on a specific outcome. We start young—eat your vegetables and you’ll get dessert—and we continue to respond to incentives all our lives.

In business, incentives are incredibly successful. Do you want your employee to do something really well? Make it a requirement in order to get a raise. Do you want your executives to accomplish something specific? Put it in their bonus plans.

And because incentives are so successful, you must create them carefully. It’s highly likely the thing you are trying to accomplish will be done to the letter, so make sure it’s exactly what you want.

If you have a shop and you want it to be clean when customers come in, it may be tempting to set a goal requiring employees to spend a certain portion of their shift cleaning. But if employees are so focused on keeping the store tidy, they neglect customers who need help, shoppers won’t be back. Your team achieved the goal you set, but that’s really not what you wanted.

Possibly the most important incentives are those created by corporate boards for their CEOs and other executives. Like any incentive, executive bonuses are highly effective, and they don’t just guide the leadership team. Because for executives to achieve their goals, the entire company, top to bottom, must work toward them too. The executive bonus plan becomes a roadmap for everyone.

For decades, increasing short term shareholder value has been the primary goal for most CEOs. Their bonus depends on it, and that bonus usually includes stock, so the CEO is highly motivated to increase the share price.

But does the board really want the stock price to increase at any cost? Or does the board want leadership to live up to other values as well?

Where is the line?

In the quest to increase shareholder value, is it OK to break the law? Ruin the environment? Endanger employees’ health?

Is it OK to pay off detractors? Hide transgressions with non-disclosure agreements? Lie to congress?

Is it OK to keep wages so low the government must step in with food stamps and other assistance? Is it OK to dodge taxes so regular citizens are left to fund the public infrastructure that makes the business possible?

As you read this, it’s not hard to think of a real-world example of each, is it?

Perhaps boards don’t overtly encourage any of this behavior, but they tacitly endorse it when they reward one kind of result without setting conditions for achieving it.

Maybe directors don’t think it through and consider what an executive team might do to accomplish their goals. Or maybe they do, but the incentive plan is still heavily weighted toward valuation, with diversity or governance or social responsibility accounting for only a small percentage of the bonus.

Here’s a suggestion.

Like an artist who thinks as much about the negative spaces in their paintings as they do about the subject, what if we thought carefully about the things we aren’t rewarding through incentive plans? What if we made a list titled, “Accomplishments for Which the Board of Directors Will Not Reward Executives?” That list might include diversity and inclusion, governance, environmental responsibility, creating engaging workplaces, treating employees with respect and dignity—things we want to see our companies accomplish in addition to increased valuation. Are we willing to admit these concerns are simply not that important?

You may have policies intended to uphold these other values, but by excluding them from the incentive plan, you’re saying that they are not as important as stock price. Is that really what you mean to say? How would you feel if your customers, employees, and shareholders saw that list? How would you defend it?

Seeing our negative spaces in that light might be uncomfortable, but it’s the way executives will see it. As long as incentive plans focus only on one thing, there’s no question where the executive team will focus, and—should things not go well in other areas—where they will try to talk their way out of difficulty.

Like it or not, changes are coming.

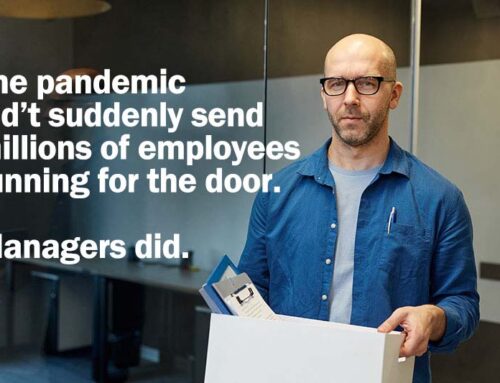

We’re in the midst of shifts we don’t fully understand. Employees emerging from the pandemic seem to be newly empowered and may have new priorities. They may leave a company because of low pay, but they may also leave because they are dissatisfied with the quality of their managers or the behavior of their companies. We must be nimble and prepared to adapt to changes in our workforces and our customers. Carefully crafted incentive plans that reward executives for improvements in diversity and inclusion, workplace culture, social responsibility, and other goals are the most effective way to accomplish that.

Changes are coming to the boardroom as well. Some investors are starting to hold executives accountable for more than profits. Notably, those investors are called “activist investors,” not “responsible investors,” or “concerned investors,” but nonetheless, they are making themselves heard. Recently, shareholders have convinced Apple to include environmental, social, and governance goals in their executive bonus plan, and an investor secured two Exxon board seats by promoting a climate agenda, so change may come there too.

But it shouldn’t take activists to make boards think hard about the kind of companies they want to create and the role those companies play in society, then use executive incentives to get it done.

It will work. It will change behavior, priorities and even company culture. Because like all of us, executives will eat as many vegetables as necessary to get their dessert.

To learn more about how to be a successful manager, read Don’t Be a Jerk Manager: The Down & Dirty Guide to Management. It’s the management training you never got, available on Kindle and in paperback from Amazon.com. The audiobook is available from Amazon, Audible and iTunes.

Do you think you might be a jerk manager? Take the quiz!

Photo by Bradyn Trollip on Unsplash